Prix : 15,00 €TTC

17-2025, tome 122, 4, p. 589-619 - Bacoup P. (2025) – Appelons une poutre une poutre : méthodes et vocabulaire pour l’étude du bois de construction préhistorique et protohistorique

Appelons une poutre une poutre

Méthodes et vocabulaire pour l'étude du bois de construction préhistorique et protohistorique

Paul Bacoup

Résumé : L'étude du bois de construction se heurte au problème bien connu de conservation du matériau ; il est rarement préservé et, lorsqu'il l'est, il présente des états de conservation variés aux possibilités d'analyses souvent limitées. En plus de ce frein inhérent à la matière en elle-même, l'archéologie de la technologie du bois d'uvre ne bénéficie pas d'une méthode propre, en particulier pour les périodes les plus anciennes, et l'absence de vocabulaire uniforme a pu nuire à la systématisation des études et a pu engendrer des incompréhensions et des erreurs d'interprétation.

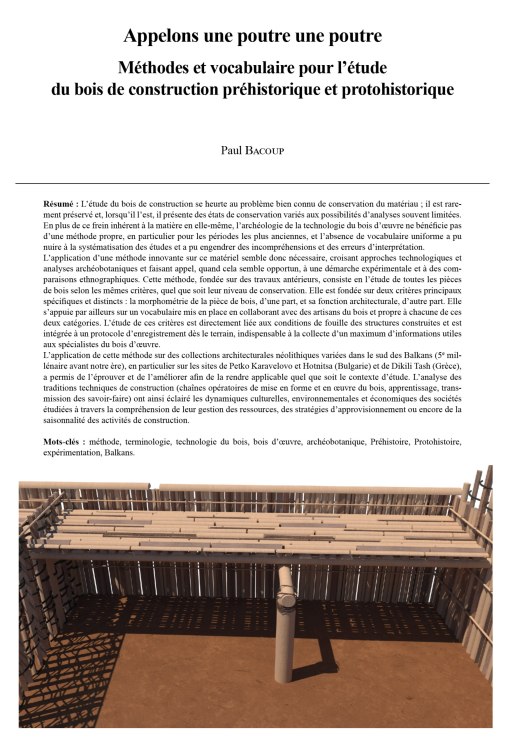

L'application d'une méthode innovante sur ce matériel semble donc nécessaire, croisant approches technologiques et analyses archéobotaniques et faisant appel, quand cela semble opportun, à une démarche expérimentale et à des comparaisons ethnographiques. Cette méthode, fondée sur des travaux antérieurs, consiste en l'étude de toutes les pièces de bois selon les mêmes critères, quel que soit leur niveau de conservation. Elle est fondée sur deux critères principaux spécifiques et distincts : la morphométrie de la pièce de bois, d'une part, et sa fonction architecturale, d'autre part. Elle s'appuie par ailleurs sur un vocabulaire mis en place en collaborant avec des artisans du bois et propre à chacune de ces deux catégories. L'étude de ces critères est directement liée aux conditions de fouille des structures construites et est intégrée à un protocole d'enregistrement dès le terrain, indispensable à la collecte d'un maximum d'informations utiles aux spécialistes du bois d'oeuvre.

L'application de cette méthode sur des collections architecturales néolithiques variées dans le sud des Balkans (5e millénaire avant notre ère), en particulier sur les sites de Petko Karavelovo et Hotnitsa (Bulgarie) et de Dikili Tash (Grèce), a permis de l'éprouver et de l'améliorer afin de la rendre applicable quel que soit le contexte d'étude. L'analyse des traditions techniques de construction (chaînes opératoires de mise en forme et en oeuvre du bois, apprentissage, transmission des savoir-faire) ont ainsi éclairé les dynamiques culturelles, environnementales et économiques des sociétés étudiées à travers la compréhension de leur gestion des ressources, des stratégies d'approvisionnement ou encore de la saisonnalité des activités de construction.

Mots-clés : méthode, terminologie, technologie du bois, bois d'oeuvre, archéobotanique, Préhistoire, Protohistoire, expérimentation, Balkans.

Abstract: The study of construction wood faces the well known issue of material preservation: wood is rarely conserved, and when it is, its state of preservation can vary significantly. These variations have led to inconsistencies in both the recording and processing of data across archaeological sites. Exceptional sites where wood has been preserved through waterlogging have been studied more extensively compared than others. Beyond this intrinsic limitation of the material, the technology of woodworking has yet to establish standardized terminology and methodology, and the absence of unified vocabulary has hindered the systematization of studies and has occasionally led to misunderstandings and misinterpretations.

To address these challenges, a method is proposed that integrates technological studies with archaeobotanical analyses. Where necessary, it also draws upon experimental approaches and ethnographic comparisons. Building on previous work in these fields, this method advocates for the systematic study of all wooden elements according to consistent criteria, regardless of whether they are preserved positively or negatively. It is based on two distinct and specific criteria: the morphometry of the wooden piece and its architectural function. A dedicated vocabulary, developed in collaboration with woodworking artisans, is proposed for each of these two categories.

Whether dealing with the wood itself or its imprints, the method requires that both dimensions and morphologies be recorded. Wooden pieces are categorized into two groups: those with circular, semi-circular, or quarter-circular cross-sections, and those with quadrangular cross-sections. Within these groups, dimensional categories are proposed, with names deliberately devoid of architectural connotations. Indeed, this approach aims to avoid assigning a functional role to a piece solely based on its morphometric characteristics.

The role of each piece of wood within the construction is reconstructed using contextual data gathered during excavation, as well as through the study of the pieces themselves and their joinery, As illustrated by the floors of Building 20 at Hotnitsa (Bulgaria, 4600???4400 BCE), which were built with three structural levels of timber: beams, joists, and floorboards. This example also perfectly illustrates the importance of maintaining the distinction between these two categories and highlights the risks of prematurely assigning functional interpretations based solely on morphometry. The wide range of architectural functions identified in prehistoric and protohistoric studies attests both to the richness of information preserved in architectural remains and to the high level of technical sophistication achieved by early builders. Once the structural role of the wooden elements has been established, it becomes possible to infer relationships between the morphometry of the wood, architectural function, construction techniques, architectural types, and their evolution (whether marked by continuity or by technical and/or social ruptures) over time and space. For example, at Petko Karavelovo, a strong technical continuity spanning nearly 800 years (5050???4300 BCE; 13 horizons) has been identified.

The combined approach of technology and archaeobotanical studies enables us to understand the criteria guiding the selection of wood species: resource availability and management, technical traditions and cultural choices, chemical properties of woods, and physical characteristics of the pieces. This is exemplified by findings at Dikili Tash (Northern Greece) during the 5th millennium BCE, where the selection of oak and ash was influenced by their fissility, despite their absence from the immediate environment. Furthermore, this method enables the recognition of standardized cutting or felling practices in certain architectural structures, as demonstrated for some wattle constructions at Petko Karavelovo.

When uncertainties remain following the technological and/or archaeobotanical study of construction wood, experimental archaeology becomes essential to confirm or refute specific hypotheses. While confirming a hypothesis suggests that it represents a plausible technical solution to the observed archaeological remains, rejecting a hypothesis can be even more instructive, as it definitively excludes that particular technical option. This process necessitates returning to archaeological material and exploring alternative techniques, often supported by ethnographic comparisons. The experimental program developed to understand earth-built walls framed by wooden double facing structures at Petko Karavelovo illustrates this aspect, as experimentation challenged and refined the technical hypotheses formulated during the study of the remains.

However, the quality of construction wood studies is directly dependent on the excavation conditions of the built structures. A protocol, tested on several Neolithic sites in the southern Balkans, is proposed here to maximize the collection of information useful for wood technology specialists already at the excavation stage. Finally, the application of this study method to prehistoric and protohistoric architectural samples in the southern Balkans (Neolithic, Chalcolithic, Bronze Age, and Iron Age) has made it possible to test and refine it, demonstrating its applicability across diverse study contexts.

Keywords: method, terminology, wood technology, construction wood, archaeobotany, Prehistory, Protohistory, experimental archaeology, Balkans.