Prix : 15,00 €TTC

09-2025, tome 122, 2, p. 253-289 - Pailler Y. et al - Brisons la hache et enterrons-la ! Autopsie et réflexions autour du dépôt d?€?une grande lame polie en fibrolite à Kerarmerrien (Plouzané, Finistère)

Brisons la hache et enterrons-la !

Autopsie et réflexions autour du dépôt d'une grande lame polie en fibrolite à Kerarmerrien (Plouzané, Finistère)

Yvan Pailler, Stéphan Hinguant, Manon Mabo, Arnaud Agranier, Vincent Bernard, Emmanuelle Collado, Rozenn Colleter, Laurence David, Olivier Poncin, Alison Sheridan, Christophe Bontemps

Résumé :

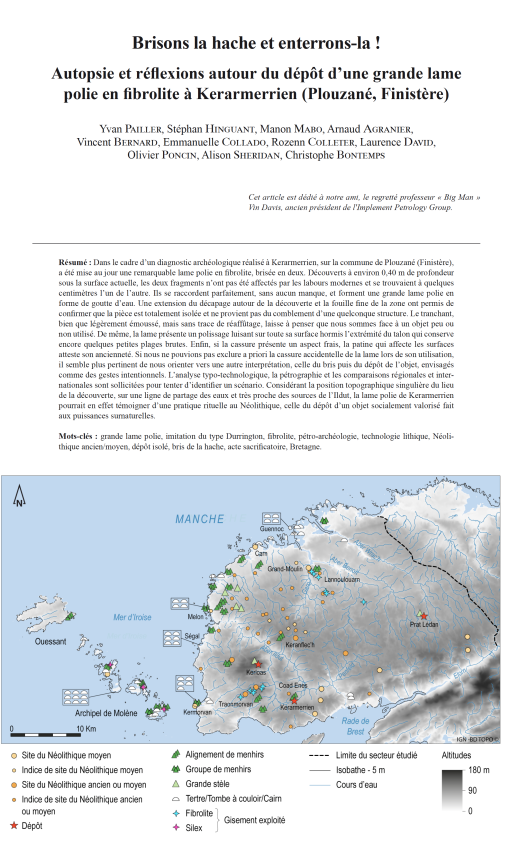

Dans le cadre d'un diagnostic archéologique réalisé à Kerarmerrien, sur la commune de Plouzané (Finistère), a été mise au jour une remarquable lame polie en fibrolite, brisée en deux. Découverts à environ 0,40 m de profondeur sous la surface actuelle, les deux fragments n'ont pas été affectés par les labours modernes et se trouvaient à quelques centimètres l'un de l'autre. Ils se raccordent parfaitement, sans aucun manque, et forment une grande lame polie en forme de goutte d'eau. Une extension du décapage autour de la découverte et la fouille fine de la zone ont permis de confirmer que la pièce est totalement isolée et ne provient pas du comblement d'une quelconque structure. Le tranchant, bien que légèrement émoussé, mais sans trace de réaffûtage, laisse à penser que nous sommes face à un objet peu ou non utilisé. De même, la lame présente un polissage luisant sur toute sa surface hormis l'extrémité du talon qui conserve encore quelques petites plages brutes. Enfin, si la cassure présente un aspect frais, la patine qui affecte les surfaces atteste son ancienneté. Si nous ne pouvions pas exclure a priori la cassure accidentelle de la lame lors de son utilisation, il semble plus pertinent de nous orienter vers une autre interprétation, celle du bris puis du dépôt de l'objet, envisagés comme des gestes intentionnels. L'analyse typo-technologique, la pétrographie et les comparaisons régionales et inter-nationales sont sollicitées pour tenter d'identifier un scénario. Considérant la position topographique singulière du lieu de la découverte, sur une ligne de partage des eaux et très proche des sources de l'Ildut, la lame polie de Kerarmerrien pourrait en effet témoigner d'une pratique rituelle au Néolithique, celle du dépôt d'un objet socialement valorisé fait aux puissances surnaturelles.

Mots-clés : grande lame polie, imitation du type Durrington, fibrolite, pétro-archéologie, technologie lithique, Néoli-thique ancien/moyen, dépôt isolé, bris de la hache, acte sacrificatoire, Bretagne.

Abstract:

During exploratory excavation of an area of 23 ha at the north-west tip of Brittany, at Kerarmerrien in Plouzané commune, two fragments of a large polished axehead were found in undisturbed ground around 40 cm below the surface. In such a large stripped area, it is remarkable that no arrangement or concentration of Neolithic material was found; this shows that the object had been deposited on its own. The only other evidence for the presence of Neolithic people consisted of several hearths with heat-damaged stones in the surrounding area; these are most likely to date to the Early or Middle Neolithic, to judge from the latest radiocarbon dates. The deposition of this axehead was situated close to the sources of the coastal river Ildut, in a large marshy depression where there is no evidence for a permanent presence of people during the Neolithic. The technical analysis of the axehead shows that it was deliberately broken in two before being buried, and the act of breakage involved a particularly strong transverse blow. The two fragments, which conjoin perfectly with one another, were laid down side by side and head-to-tail, showing a clear intention to position them. The axehead, of an exceptional size (almost 23 cm long), must have taken hundreds of hours to manu-facture, involving hammering, sawing and polishing. Macroscopically, the raw material is a massive fibrolite, green-ish-yellow with brown patches; its interdigitated fibrous structure is typical of that seen at the outcrops at Plouguin. The results of geochemical analyses (by XRF and Raman spectrometry), compared with those of several raw material samples collected through prospecting, confirm that this is a sillimanite with muscovite, identical to that of the Plouguin outcrops, and more specifically to those at Lanrivanan, in the same commune, just 19 km to the north of the axehead findspot as the crow flies. The axehead, obtained through sawing (as is shown by the asymmetry of its cross-section), is in the form of a teardrop, reminiscent of the Durrington type of axehead made from Alpine rock. The Durrington type, like the Heilles type with which the axehead also shares formal similarities, had a fairly long currency, appearing during the Early Neolithic and disappearing during the Middle Neolithic 2. There is evidence for Neolithic activity during this period in bas Léon, with the number of B-VSG finds multiplying, while the Middle Neolithic evidence (in the form of passage tombs, arrangements of standing stones, settlements and fish weirs) reveals a certain patterning in the spatial organisation of activities.

The Kerarmerrien find spurred us to re-examine the deposits of axeheads that had been made in Brittany, comparing them with deposits of axeheads made from Alpine rocks that have recently been the subject of synthesis and thorough documentation by JADE project (directed by Pierre Pétrequin). Our attention was drawn to an old find (1970), of a complete axe with its haft, brought to the surface through shallow dredging in the Trieux estuary (Côtes-d'Armor), next to a bog. This is known only from a brief mention in a publication. While the haft could not be conserved, photographs taken shortly after its discovery allow us to make out its shape and size, and to draw a parallel with axes known in the Pfyn culture (Switzerland) dating to the first third of the 4th millennium; in these, the head was slotted directly into the haft and the upper end of the haft curves backwards slightly. The large axehead that was found in its haft at Trieux had a perfectly sharp blade and was made from a chrome-rich muscovite with sillimanite -- the chrome explaining the very green patches visible on the surface -- which points towards the outcrops of Plouguin, in north-west Finistère, as the origin. Rather than imagining a simple loss of this tool as someone crossed a small coastal river, it seems to us more likely that we are dealing with a case of deliberate deposition, connected with the water.

Several other findspots in Armorica and elsewhere suggest a deliberate choice of location for axehead deposition (the commonest being on high ground, or close to water, or at a rocky outcrop or beside a standing stone), generally at some distance from settlements or tombs. While the location of the findspot was important, it seems that the manner in which the axeheads were deposited similarly played a key role. Here, the observations made in situ at Plouzané, Carentoir and Lannion offer new insights on the complex question of depositional practices. To this we can add instances where axeheads have been associated with objects that do not seem special but which appear to us, with our prehistorians' eyes, to relate to the everyday. But, finally, what do we know of the biographies of these polished axeheads outside of their place of discovery; of their chaîne opératoire; and, in certain cases, of the outcrops from which their raw material had been extracted?

Keywords: large polished axehead, teardrop shape, fibrolite, petro-archaeology, lithic technology, Early/Middle Neolithic, isolated deposition, breakage of an axehead, sacrificial act, Brittany.