- La SPF

- Réunions

- Le Bulletin de la SPF

- Accès libre Jstor (1978-2023)

- Accès libre Persée (1904-2021)

- Bulletin de la SPF 2025, tome 122

- Bulletin de la SPF 2024, tome 121

- Bulletin de la SPF 2023, tome 120

- Bulletin de la SPF 2022, tome 119

- Séances de la SPF (suppléments)

- Organisation et comité de rédaction

- Comité de lecture (2020-2025)

- Ligne éditoriale et consignes BSPF

- Données supplémentaires

- Annoncer

- Publications

- Vidéo

- Newsletter

- Boutique

Prix : 15,00 €TTC

13-2025, tome 122, 3, p, 405-457 - Pétrequin P., Pétrequin A.-M., Cassen S., Costa E., Buthod-Ruffier D., Errera M., Lepère C., Mabo M., Prodéo F., Sheridan A. (2025) – Au royaume de Carnac (Morbihan) au milieu du Ve millénaire : les haches polies en fibr

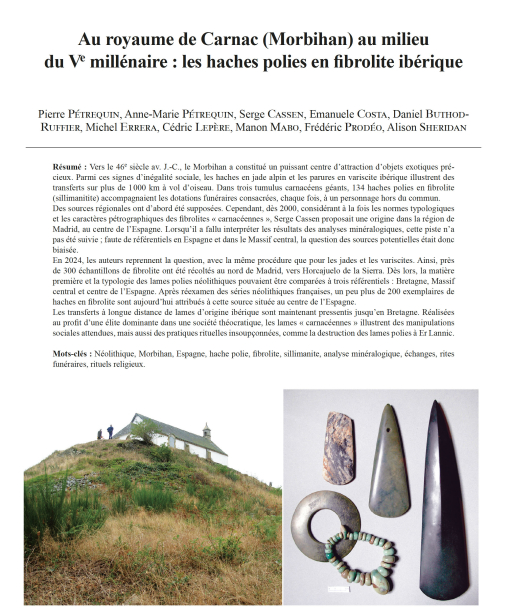

Au royaume de Carnac (Morbihan) au milieu ???du Ve millénaire : les haches polies en fibrolite ibérique

Pierre Pétrequin, Anne-Marie Pétrequin, Serge Cassen, Emanuele Costa, Daniel Buthod-Ruffier, Michel Errera, Cédric Lepère, Manon Mabo, Frédéric Prodéo, Alison Sheridan

Résumé : Vers le 46e siècle av. J.-C., le Morbihan a constitué un puissant centre d'attraction d'objets exotiques précieux. Parmi ces signes d'inégalité sociale, les haches en jade alpin et les parures en variscite ibérique illustrent des transferts sur plus de 1 000 km à vol d'oiseau. Dans trois tumulus carnacéens géants, 134 haches polies en fibrolite (sillimanitite) accompagnaient les dotations funéraires consacrées, chaque fois, à un personnage hors du commun.

Des sources régionales ont d'abord été supposées. Cependant, dès 2000, considérant à la fois les normes typologiques et les caractères pétrographiques des fibrolites « carnacéennes », Serge Cassen proposait une origine dans la région de Madrid, au centre de l'Espagne. Lorsqu'il a fallu interpréter les résultats des analyses minéralogiques, cette piste n'a pas été suivie ; faute de référentiels en Espagne et dans le Massif central, la question des sources potentielles était donc biaisée.

En 2024, les auteurs reprennent la question, avec la même procédure que pour les jades et les variscites. Ainsi, près de 300 échantillons de fibrolite ont été récoltés au nord de Madrid, vers Horcajuelo de la Sierra. Dès lors, la matière première et la typologie des lames polies néolithiques pouvaient être comparées à trois référentiels : Bretagne, Massif central et centre de l'Espagne. Après réexamen des séries néolithiques françaises, un peu plus de 200 exemplaires de haches en fibrolite sont aujourd'hui attribués à cette source située au centre de l'Espagne.

Les transferts à longue distance de lames d'origine ibérique sont maintenant pressentis jusqu'en Bretagne. Réalisées au profit d'une élite dominante dans une société théocratique, les lames « carnacéennes » illustrent des manipulations sociales attendues, mais aussi des pratiques rituelles insoupçonnées, comme la destruction des lames polies à Er Lannic.

Mots-clés : Néolithique, Morbihan, Espagne, hache polie, fibrolite, sillimanite, analyse minéralogique, échanges, rites funéraires, rituels religieux.

Abstract: On the Morbihan coast, three gigantic mounds each covered a single chamber, made to accommodate a person accompanied by a very rich grave assemblage. This gave rise to the hypothesis that, between 4600 and 4300 BC, the society in the Carnac area was based on a system of religious beliefs that supported an elite dominated by a "god-king".

Mané er Hroëck at Locmariaquer is the oldest, and most richly-equipped of these Carnac monuments, containing 12 large polished axeheads and an arm-ring of jade, a long axehead of serpentinite, 49 beads and pendants of variscite and no fewer than 92 polished blades of fibrolite (sillimanitite). Thus we are dealing with an exceptional concentration of extraordinary wealth, with the jades originating in the Alps (Monte Viso, Monte Beigua, Moiry and Gemsstock) and the variscite in Spain (Encinasola). The Morbihan was thus at the heart of a system that drew in precious items from distant sources, 1 000 or more kilometres away. We have been able to demonstrate this by comparing the objects of jade and variscite with our raw material reference collections, comprising thousands of samples collected in the Alps and the Iberian peninsula.

Pinpointing the sources of axe- and adze-heads of fibrolite is harder. Several more or less significant outcrops are known in Finistère, the Massif central and Spain. However, researchers have only been able to draw conclusions according to the raw material samples at their disposal and the different regional typology of axeheads. Thus, for Alexis Damour in 1865, the fibrolite polished blades from Mané er Hroëck were thought to originate in the Massif central. According to Louis Marsille in 1920, the source was claimed to be the Morbihan coast, where this rock was collected in the form of cobbles. In 1952, Jean Cogné and Pierre-Roland Giot observed that at least four Breton sources could have been exploited, and concluded that this "ordinary" rock would not have had a particular value. In contrast, Charles-Tanguy Le Roux in 1979 underlined the special nature of the "Carnac style" axe- and adze-heads of fibrolite, which had no convincing match in Brittany.

The blades found at Mané er Hroëck (like those from Tumiac at Arzon and Mont Saint-Michel at Carnac) will have been long-distance imports, worthy of inclusion in the grave of a god-king. Since 2000, this hypothesis has been put forward by Serge Cassen, following his comparison of these blades with those from the area around Madrid. Cassen's suggestion was not, however, followed up by geologists in the interpretation of the results of the mineralogical analyses undertaken since 2009, among which are those for the adzehead found in the chamber of Lannec er Gadouer at Erdeven. Without a raw material reference collection that included specimens from outside Brittany, the identification of potential sources was necessarily biased.

In April 2004, we took the next step in fieldwork in order to fill the gap in the raw material reference collection - just as we had done in the case of jades and variscite. Our prospection in the Rincòn basin north of Madrid enabled us to gather nearly 300 samples of fibrolite, then in November, to observe in the Auvergne a further c. 200 axeheads out of fibrolite.

As a result it has been possible to open the field of comparison to areas outside of Brittany and seek the closest comparanda for the blades of Mané er Hroëck. A striking resemblance was noted between these axe- and adze-heads in the Morbihan and the samples from Horcajuelo de la Sierra; in contrast, the Massif central can now be ruled out of the list of plausible comparanda. Serge Cassen's hypothesis has therefore been reactivated ??? with all the more reason, given his observation that the Spanish and Morbihannais fibrolite axe- and adze-heads share the same "archaeological" characteristics.

Thus, the importation of Iberian fibrolite axe- and adze-heads has been confirmed; what remains is to clarify the scale of the phenomenon in France. Currently, nearly 200 polished blades can be shown to have been made of Horcajuelo fibrolite - and, possibly, of fibrolite more broadly from the Guadarrama and North Madrid sierras. Most have come from funerary contexts in the Morbihan. Their cutting edge shows no sign of use; this underlines the status of these adze-heads as being the preserve of a handful of individuals. Spanish fibrolite blades are also found in mounds of more modest proportions in southern Brittany and the Vendée coast. There can be no doubt of the association of these blades with "Carnac society".

Outside of the funerary context, Iberian blades are rare. Often they were treated in unusual ways. They have been identified at the foot of an alignment of standing stones, at Groah Denn on the island of Hoëdic. Four miniature axeheads, made by reworking full-sized Carnac blades of fibrolite, have been found at Gavrinis. But a surprise was to demonstrate that at Er Lannic - a so-called workshop for producing blades ??? numerous fibrolite examples had been imported. Moreover, they had been broken using heavy blows of a stone hammer; it is hard to escape the idea that some kind of sacrifice was going on here, in a religious context underlined by the presence of an extraordinary number of Castellic-style "incense burners".

In the Morbihan, the polished blades of Iberian fibrolite must have formed part of the ensemble of long-distance movements, along with items of jades and of variscite. The elite of the Carnac area played a strategic role in the process of attracting and manipulating these objects of wealth. We must, however, try to understand the specific status of the polished blades of fibrolite, as at Mané er Hroëck, where they were grouped separately from the objects of jades and of variscite. One also needs to ask why the axe- and adze-heads of Iberian fibrolite seem not to have featured in the large non-funerary deposits such as that of Bernon at Arzon, which consists entirely of axeheads of Alpine jades.

Keywords: Neolithic, Morbihan, Spain, polished axehead, fibrolite, sillimanite, mineralogical analysis, exchanges, funerary rites, religious rituals.

Autres articles de " Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française 2025"

18-2025, tome 122, 4, p, 621-647 - Ghesquière E., Auxiette G., Dupont C., Giazzon D., Le Guévellou R., Marcigny C., Coupard F. (2025) – L’enceinte elliptique du Bronze ancien de Blainville-sur-Orne (Calvados) et son environnement,

L'enceinte elliptique du Bronze ancien de Blainville-sur-Orne (Calvados) et son environnement

Emmanuel Ghesquière, Ginette Auxiette, Catherine Dupont, David Giazzon, Roland Le Guévellou, Cyril Marcigny, François Coupard

Résumé : Un diagnostic en 2017 et une fouille en 2019 ont révélé la présence d'une enceinte elliptique d'un peu plus de 2 000 m² de surface interne, délimitée par un profond fossé qui présente une interruption à l'est. L'intérieur de l'enceinte ne révèle pas d'autres structures conservées qu'une cave rectangulaire adossée au fossé et une série de linéaments au centre qui pourraient correspondre à des fantômes de structures bâties. Le mobilier découvert dans le fossé est assez abondant, livrant le plus gros assemblage céramique du Bronze ancien 2 régional. L'industrie lithique est un peu moins fréquente mais reste caractéristique de l'âge du Bronze. La faune est bien représentée, dominée par le boeuf. La répartition et le choix des os déposés témoigneraient de pratiques spécifiques, éventuellement liées à des banquets. Les éléments crâniens sont particulièrement nombreux et concentrés sur la façade orientale, et ce, sur l'ensemble du remplissage du fossé. On note également la présence de deux chiens et d'un os de grand cétacé. Deux fragments d'outils perforés sur meule de bois de cerf pourraient correspondre à des outils contondants. L'environnement du site est partiellement connu grâce à d'autres diagnostics et fouilles. Il comprend plusieurs groupes funéraires dispersés, du Bronze ancien ou non datés, autour de petits enclos circulaires. Des structures parcellaires partielles de la même période ont également été mises en évidence à 600 m au nord. Un axe viaire borde le fossé d'enceinte, nettement infléchi à ce niveau-là. Ce chemin se prolonge de façon sinueuse sur plus de 800 m. Vers l'ouest, ce dernier rejoint l'Orne, modeste fleuve navigable qui se jette dans la Manche à huit kilomètres au nord. Cet article reprend l'ensemble des caractéristiques de l'enceinte en la comparant aux structures similaires découvertes en Normandie et en Grande-Bretagne, en soulignant son possible rôle élitaire et son association avec les probables groupes funéraires qui l'entourent.

Mots-clés : enceinte, enclos funéraire, Bronze ancien, parcellaire, céramique, silex.

Abstract: An evaluation conducted in 2017, followed by an excavation in 2019, revealed an elliptical enclosure covering an internal area of just over 2,000 m², defined by a deep ditch interrupted on its eastern side. Within the enclosure, no other clearly preserved features were identified apart from a rectangular cellar abutting the ditch and a series of linear traces in the centre, possibly representing the remains of built structures. The ditch yielded the largest pottery assemblage attributable to the Early Bronze Age 2, while the few lithic artefacts recovered are also characteristic of this period. The faunal remains are well preserved and consist predominantly of cattle, whose distribution and selection suggest depositional practices possibly linked to feasting. Cranial bones are particularly numerous and concentrated along the eastern façade, extending throughout the entire infilling of the ditch. Additionally, two dog remains and a large cetacean bone were recovered. Two fragments of perforated deer antler tools may have served as percussive implements.

The site's wider environment has been investigated during previous evaluations and excavations, revealing several dispersed funerary groups situated around small circular enclosures dating to the Early Bronze Age or of uncertain date. Partial features of the same period have also been recorded approximately 600 m to the north. A road axis runs alongside the enclosure ditch, showing a marked inflection at this point; this route continues in a sinuous course for over 800 m and, to the west, joins the Orne River - a small navigable waterway flowing into the English Channel some eight kilometres to the north.

This paper re-examines the enclosure's characteristics in comparison with analogous structures identified in Normandy and Great Britain, highlighting its potential role as an elite site and its likely association with the surrounding funerary groups.

Keywords: enclosure, funerary enclosure, early bronze, plot, ceramic, flint.

17-2025, tome 122, 4, p. 589-619 - Bacoup P. (2025) – Appelons une poutre une poutre : méthodes et vocabulaire pour l’étude du bois de construction préhistorique et protohistorique

Appelons une poutre une poutre

Méthodes et vocabulaire pour l'étude du bois de construction préhistorique et protohistorique

Paul Bacoup

Résumé : L'étude du bois de construction se heurte au problème bien connu de conservation du matériau ; il est rarement préservé et, lorsqu'il l'est, il présente des états de conservation variés aux possibilités d'analyses souvent limitées. En plus de ce frein inhérent à la matière en elle-même, l'archéologie de la technologie du bois d'uvre ne bénéficie pas d'une méthode propre, en particulier pour les périodes les plus anciennes, et l'absence de vocabulaire uniforme a pu nuire à la systématisation des études et a pu engendrer des incompréhensions et des erreurs d'interprétation.

L'application d'une méthode innovante sur ce matériel semble donc nécessaire, croisant approches technologiques et analyses archéobotaniques et faisant appel, quand cela semble opportun, à une démarche expérimentale et à des comparaisons ethnographiques. Cette méthode, fondée sur des travaux antérieurs, consiste en l'étude de toutes les pièces de bois selon les mêmes critères, quel que soit leur niveau de conservation. Elle est fondée sur deux critères principaux spécifiques et distincts : la morphométrie de la pièce de bois, d'une part, et sa fonction architecturale, d'autre part. Elle s'appuie par ailleurs sur un vocabulaire mis en place en collaborant avec des artisans du bois et propre à chacune de ces deux catégories. L'étude de ces critères est directement liée aux conditions de fouille des structures construites et est intégrée à un protocole d'enregistrement dès le terrain, indispensable à la collecte d'un maximum d'informations utiles aux spécialistes du bois d'oeuvre.

L'application de cette méthode sur des collections architecturales néolithiques variées dans le sud des Balkans (5e millénaire avant notre ère), en particulier sur les sites de Petko Karavelovo et Hotnitsa (Bulgarie) et de Dikili Tash (Grèce), a permis de l'éprouver et de l'améliorer afin de la rendre applicable quel que soit le contexte d'étude. L'analyse des traditions techniques de construction (chaînes opératoires de mise en forme et en oeuvre du bois, apprentissage, transmission des savoir-faire) ont ainsi éclairé les dynamiques culturelles, environnementales et économiques des sociétés étudiées à travers la compréhension de leur gestion des ressources, des stratégies d'approvisionnement ou encore de la saisonnalité des activités de construction.

Mots-clés : méthode, terminologie, technologie du bois, bois d'oeuvre, archéobotanique, Préhistoire, Protohistoire, expérimentation, Balkans.

Abstract: The study of construction wood faces the well known issue of material preservation: wood is rarely conserved, and when it is, its state of preservation can vary significantly. These variations have led to inconsistencies in both the recording and processing of data across archaeological sites. Exceptional sites where wood has been preserved through waterlogging have been studied more extensively compared than others. Beyond this intrinsic limitation of the material, the technology of woodworking has yet to establish standardized terminology and methodology, and the absence of unified vocabulary has hindered the systematization of studies and has occasionally led to misunderstandings and misinterpretations.

To address these challenges, a method is proposed that integrates technological studies with archaeobotanical analyses. Where necessary, it also draws upon experimental approaches and ethnographic comparisons. Building on previous work in these fields, this method advocates for the systematic study of all wooden elements according to consistent criteria, regardless of whether they are preserved positively or negatively. It is based on two distinct and specific criteria: the morphometry of the wooden piece and its architectural function. A dedicated vocabulary, developed in collaboration with woodworking artisans, is proposed for each of these two categories.

Whether dealing with the wood itself or its imprints, the method requires that both dimensions and morphologies be recorded. Wooden pieces are categorized into two groups: those with circular, semi-circular, or quarter-circular cross-sections, and those with quadrangular cross-sections. Within these groups, dimensional categories are proposed, with names deliberately devoid of architectural connotations. Indeed, this approach aims to avoid assigning a functional role to a piece solely based on its morphometric characteristics.

The role of each piece of wood within the construction is reconstructed using contextual data gathered during excavation, as well as through the study of the pieces themselves and their joinery, As illustrated by the floors of Building 20 at Hotnitsa (Bulgaria, 4600???4400 BCE), which were built with three structural levels of timber: beams, joists, and floorboards. This example also perfectly illustrates the importance of maintaining the distinction between these two categories and highlights the risks of prematurely assigning functional interpretations based solely on morphometry. The wide range of architectural functions identified in prehistoric and protohistoric studies attests both to the richness of information preserved in architectural remains and to the high level of technical sophistication achieved by early builders. Once the structural role of the wooden elements has been established, it becomes possible to infer relationships between the morphometry of the wood, architectural function, construction techniques, architectural types, and their evolution (whether marked by continuity or by technical and/or social ruptures) over time and space. For example, at Petko Karavelovo, a strong technical continuity spanning nearly 800 years (5050???4300 BCE; 13 horizons) has been identified.

The combined approach of technology and archaeobotanical studies enables us to understand the criteria guiding the selection of wood species: resource availability and management, technical traditions and cultural choices, chemical properties of woods, and physical characteristics of the pieces. This is exemplified by findings at Dikili Tash (Northern Greece) during the 5th millennium BCE, where the selection of oak and ash was influenced by their fissility, despite their absence from the immediate environment. Furthermore, this method enables the recognition of standardized cutting or felling practices in certain architectural structures, as demonstrated for some wattle constructions at Petko Karavelovo.

When uncertainties remain following the technological and/or archaeobotanical study of construction wood, experimental archaeology becomes essential to confirm or refute specific hypotheses. While confirming a hypothesis suggests that it represents a plausible technical solution to the observed archaeological remains, rejecting a hypothesis can be even more instructive, as it definitively excludes that particular technical option. This process necessitates returning to archaeological material and exploring alternative techniques, often supported by ethnographic comparisons. The experimental program developed to understand earth-built walls framed by wooden double facing structures at Petko Karavelovo illustrates this aspect, as experimentation challenged and refined the technical hypotheses formulated during the study of the remains.

However, the quality of construction wood studies is directly dependent on the excavation conditions of the built structures. A protocol, tested on several Neolithic sites in the southern Balkans, is proposed here to maximize the collection of information useful for wood technology specialists already at the excavation stage. Finally, the application of this study method to prehistoric and protohistoric architectural samples in the southern Balkans (Neolithic, Chalcolithic, Bronze Age, and Iron Age) has made it possible to test and refine it, demonstrating its applicability across diverse study contexts.

Keywords: method, terminology, wood technology, construction wood, archaeobotany, Prehistory, Protohistory, experimental archaeology, Balkans.

16-2025, tome 122, 4, p. 579-588 - Pigeaud R. (2025) – Grotte ornée ou grotte ornante : interrogations autour d’un adjectif

Grotte ornée ou grotte ornante : interrogations autour d'un adjectif

Romain Pigeaud

Résumé : Le terme de « grotte ornée » fut inventé par Gabriel de Mortillet à une époque où l'art des cavernes était envisagé comme un simple passe-temps, dans le cadre de la théorie de « l'art pour l'art ». Cette théorie abandonnée, il fut néanmoins maintenu par commodité et par tradition, bien qu'il soit totalement inadapté et puisse parfois être envisagé comme dépréciatif.

Nous rappelons la généalogie du terme « orné », qui renvoie à des débats esthétiques de la fin du xixe siècle, où la question de l'ornement et des débuts de l'art figuratif faisait l'objet de débats passionnés, en parallèle avec le développement de la science préhistorique, de l'ethnologie et de l'étude des dessins d'enfants. Nous inspirant des travaux de la philosophe Baldine Saint-Girons, nous proposons de le remplacer par « grotte ornante », qui traduit plus justement le processus d'appropriation symbolique de l'espace souterrain, dans une démarche anthropologique et processuelle.

Mots-clés : grotte ornée, grotte ornante, ornement, décoration, anthropologie, épistémologie, art pariétal.

Abstract: The term ???decorated cave??? was coined by Gabriel de Mortillet in a posthumous article, at a time when cave art was considered a mere pastime, within the framework of the theory of ???art for art's sake???. This theory was abandoned, but it was nevertheless retained for convenience and tradition, although it is completely inappropriate and can sometimes be considered derogatory. This poses a problem, because why do drawings considered useful most often present evidence of aesthetic research? Was the beauty of cave art superfluous? How can we escape these value judgments? Some prehistorians will thus propose reserving the term "decorate" for cavities whose decoration seems to them to be the most carefully crafted. As tastes change with the generations, this would open the door to endless discussions.

We recall the genealogy of the term "decorate", which refers to aesthetic debates of the late 19th century, when the question of ornament and the beginnings of figurative art was the subject of heated debates, alongside the development of prehistoric science, ethnology, and the study of children's drawings. Émile Cartailhac in particular used the metaphor of "tapestry", which disconnected Paleolithic drawings from their support, like added motifs, whereas we know today the total interweaving of these with the relief, the volumes of the walls and the topography of the underground space. The cave is "organizing" and no longer "participating", "domesticated" by Paleolithic groups who anthropize the places by modifying the structure of the galleries, the directions of circulation as well as the viewpoints and the staging of drawn panels. Inspired by the work of the philosopher Baldine Saint-Girons, we propose replacing it with "adorning cave", which more accurately reflects the process of symbolic appropriation of underground space, in an anthropological and processual approach.

Keywords: decorated cave, adorning cave, ornament, decoration, anthropology, epistemology, parietal art.

15-2025, tome 122, 4, p. 527-578 - Goutas N., Legrand A., Bourdier C., Feruglio V., Brochard E., Lefebvre A., López-Polín L., McGrath K., Fourment N., Geneste J.-M., Mora P., Muth X., Tisnérat-Laborde N., Jaubert J. (2025) – Un outil de gravure en bois de

Un outil de gravure en bois de cervidé dans la grotte de Cussac (Dordogne, France) ?

Analyses et discussions autour d'un objet particulier découvert à près de 620 m de l'entrée

Nejma Goutas, Alexandra Legrand, Camille Bourdier, Valérie Feruglio, Émilie Brochard, Alexandre Lefebvre, Lucía López-Polín, Krista McGrath, Nathalie Fourment, Jean-Michel Geneste, Pascal Mora, Xavier Muth, Nadine Tisnérat-Laborde, Jacques Jaubert

Résumé : La grotte ornée et sépulcrale de Cussac a livré pour l'heure un unique objet en matière osseuse (appointé mousse), retrouvé isolé, cassé et à une grande distance de l'entrée. Les étapes et résultats de sa chaîne d'analyse - ici présentés - permettent de suivre la démarche inductive qui nous a conduits à nous interroger sur son possible usage en outil de gravure pariétale. Cette hypothèse prend appui sur les résultats de l'analyse de l'objet croisés aux autres données archéologiques disponibles. Pour tester cette hypothèse, l'analyse tracéologique de l'objet a été adossée à un volet expérimental conduit dans une cavité offrant un environnement géologique comparable à celui de Cussac afin de disposer d'un premier référentiel de traces d'usure générées sur outils en bois de cervidés par l'acte de graver. Les résultats de notre étude sont les suivants : l'objet (env. 200 mm de long pour 10 mm de large et d'épaisseur) est façonné sur un tronçon de bois de renne de petit module ; son histoire post-dépositionnelle est complexe ; son morphotype le rapproche d'autres découvertes, pour l'heure, uniquement reconnues en contextes gravettiens. Il se démarque toutefois par le soin apporté à sa fabrication et le statut fonctionnel du lieu de sa découverte. Son attribution chronoculturelle, en l'absence de datation radiométrique (essai infructueux), fait toutefois écho aux données de l'art pariétal, de l'industrie lithique et aux datations 14C sur charbons de bois et un reste humain. Son analyse fonctionnelle a permis d'identifier une extrémité active (et une autre potentielle) et d'en inférer un mode de fonctionnement. Ce dernier, ainsi que les stigmates fonctionnels et les propriétés morpho-structurelles de l'objet sont notamment incompatibles avec une utilisation en armature de projectile, compresseur, outil intermédiaire ou outil perforant. Parallèlement, des correspondances tracéologiques ont été établies avec les outils expérimentaux que nous avons utilisés. L'ensemble de ces données, avec les précautions nécessaires, autorise à considérer l'hypothèse d'outil de gravure pariétale comme « opératoire », à défaut d'être pleinement démonstrative et a minima, elles ne l'invalident pas. Cette étude constitue une base de travail didactique inédite. La pièce de Cussac est en effet le premier outil en matière osseuse (et le seul manufacturé) pour lequel cette hypothèse est examinée sur la base d'une étude détaillée des stigmates techniques et fonctionnels et d'un volet expérimental exploratoire.

Mots-clés : Cussac, grotte, Gravettien, art pariétal, industrie osseuse, outil de gravure, technologie, tracéologie, démarche expérimentale.

Abstract: The bone industry discovered in Cussac Cave (Dordogne, France) is represented by three fragmentary, associated elements, whose structural, morphometric, and technological characteristics permit attribution to a single long, cylindrical, and pointed antler artifact. Isolated and found at a considerable distance (ca. 618 m) from the entrance of the cave, it is of significant interest both in terms of its potential chrono-cultural attribution and its presumed function. After being lost or abandoned, this object underwent various taphonomic alterations. Discovered broken, encrusted, and adhering to the floor of the cave, it raised several questions with regard to its raw material, chrono-cultural attribution, status as a processing tool as opposed to a piece of hunting equipment, its - operating mode - (according to the translation given in Guéret et al., 2014 of 'mode de fonctionnement') and its "technical function" (sensu Claud et al., 2019), and reasons for its presence in the cave. The different steps in its analysis and associated results are presented here, including in situ observations, sampling, restoration, taphonomic and techno-functional analyses, ZooMS identification, and 14C dating. They permit the reader to follow the inductive approach that guided our investigations and led us from empirical elements placed in perspective (on the object itself and its archaeological context) to explore a possible use of the Cussac object as an engraving tool in the production of parietal art. Notably, the cave contains rock art panels (e.g., the Réticulé panel in the downstream branch) with markings consistent with the use of a soft-tipped organic tool (as concluded from a 2022 published experimental study on the morphometric characterization of marks produced by different objects).

To test the plausibility of this hypothesis, the use-wear analysis of the object was complemented with an exploratory experimental component conducted in a neighboring cavity with a comparable geological environment, providing a preliminary reference for wear traces generated by engraving with antler tools (performed on weathered limestone and, to a lesser extent, on clay).

Based on this study, the following results can be reported: the object likely measured approximately 200 mm in length and 10 mm in width and thickness in its original state; it was shaped from a small-diameter reindeer antler segment (possibly a beam). Moreover, its post-depositional history is complex; its morphotype links it to other discoveries, currently recognized only in Gravettian contexts. However, it stands out due to the care of its manufacture and the status of its place of discovery in a rock art burial cave. While direct dating of the object was unsuccessful due to insufficient collagen preservation, its chrono-cultural attribution corresponds with stylistic evidence from the parietal art as well as other elements, such as radiocarbon dating of charcoal and human remains and the chronological attributions of the few lithic artifacts recovered in the cave.

The analysis identified macro- and microscopic functional marks, the nature and organization of which permit, on one hand, the identification of an active part, round-tipped and bearing short transverse incisions (and a potential second one); and, on the other hand, the inference for its operating mode. This involved a deliberate rubbing action, performed with an acute rake angle, involving brief but repeated and continuous contact of the working surface with a relatively supple but not soft material, and intermittent contact of the apex with a harder material. However, the preserved and observable wear areas do not fully represent the full extent of its original appearance due to taphonomic effects and the porous nature of bone surfaces, and must therefore be considered as a minimal approximation. It can nevertheless be noted that the object's operating mode and structural properties are incompatible with use involving high mechanical stress. At the same time, the associated nature and pattern of its use-wear traces and the non-cutting, non-piercing, non-perforating character of the object exclude its use as a hunting weapon, as an intermediary tool, an perforating tool or a pressure flaker, as well as use as a soil- or termite-excavating tool unlikely, based on reference collections used in this study. These observations allowed us to narrow down plausible functional hypotheses. At the same time, use-wear analysis correspondences were established with the experimental tools used. We thus propose, with all necessary caution, to consider it as a possible engraving tool, while remaining aware of the interpretive limits of reasoning from a single object, particularly one with a complex preservation history. This limitation is primarily circumstantial, as no other bone tools potentially associated with engraving activities have, to date, been studied from a functional perspective.

The contributions and limitations of our experimental approach are also discussed, notably the number of experimental tests conducted and the raw material used for the experimental tools. While further experiments could enrich the reference framework and improve the protocol, the results presented in this article permit - with necessary precaution - the hypothesis of a parietal engraving tool to be considered "operational," if not fully demonstrable, and at minimum, they do not invalidate it. The state of preservation of the object and its unique status that precludes comparison with other such specimens remain a limitation that cannot be overcome at present.

Our review of reported or potential cases of engraving tools in Palaeolithic cave contexts shows that the Cussac piece constitutes the first bone tool ??? and the only manufactured one ??? for which this hypothesis is discussed based on a detailed study of technical and functional attributes, combined with an experimental component. In this sense, the study provides an unprecedented didactic basis from which to address these questions. More specifically, it contributes to our understanding of and questions concerning the relationship between underground environments and material culture at Cussac Cave.

Keywords: Cussac, cave, Gravettian, parietal art, bone industry, engraving tool, technology, traceology, experimental approach.

14-2025, tome 122, 3, p. 459-473 - Strobel M., Bruschke B., Noack K. (2025) – Entre la Haute-Lusace prussienne et Paris : recherches archéologiques sur des campements mésolithiques dans l’oflag IV D Elsterhorst (Hoyerswerda, Saxe, Allemagne) par des offic

Entre la Haute-Lusace prussienne et Paris - Études archéologiques sur des campements mésolithiques à l'oflag IV D Elsterhorst (Hoyerswerda, Saxe, Allemagne) menées par des officiers français

Michael Strobel, Bettina Bruschke, Kerstin Noack avec la collaboration de Julia Kiontke et Max Schneider

Résumé : Entre l'été 1940 et le printemps 1945, environ 5 000 à 6 000 officiers français ont été internés dans l'oflag IV D « Elsterhorst » près de Hoyerswerda (Saxe, Allemagne). Des traces de ce camp de trente hectares entouré de barbelés sont aujourd'hui conservées dans la prairie d'un terrain de vol à voile et sont visibles depuis les airs. C'est notamment le cas des fondations des différents baraquements qu'il est possible de localiser et de géoréférencer précisément sur la base de photos aériennes. Dans la mesure où les statuts de la convention de Genève permettaient aux officiers d'être exemptés de tous travaux, différents espaces d'activités ont été aménagés, comme des jardins ainsi que des terrains de tennis et de football. En outre, les prisonniers de guerre ont créé une « université » et un théâtre. Durant l'été 1941, un groupe de travail archéologique de onze personnes s'est formé sous la direction de Louis-René Nougier (1912-1995). Leurs recherches, menées lors de « promenades », conduisirent à la découverte et à l'étude de plusieurs gisements mésolithiques au sein du camp. La plupart d'entre eux étaient membres de la Société préhistorique française, entretenaient des échanges étroits avec le siège de leur association à Paris et étaient soutenus par le directeur du musée d'Hoyerswerda, Otto Damerau. En juillet 1950, le groupe de travail a pu faire part de ses recherches dans l'oflag IV D lors du 13e Congrès préhistorique de France, qui eut lieu à Paris.

Mots-clés : Allemagne, camps de prisonniers de guerre, oflag IV D Elsterhorst, officiers français, Société préhistorique française, histoire de la recherche, Mésolithique.

Abstract: Between summer 1940 and spring 1945, around 5,000 to 6,000 French officers were interned in Oflag IV D "Elsterhorst" near Hoyerswerda (Saxony, Germany). Traces of the 30-hectare, barbed-wire fenced camp can still be seen today in the meadow area of a glider airfield and are visible from the air. This is particularly true of the foundations of the residential and functional barracks. On the basis of historical and current aerial photographs, it is possible to precisely localise and georeference the structures. As the officers were not allowed to be put to work according to the statutes of the Geneva Convention, there were numerous areas for various activities such as gardens, tennis courts and football pitches. The prisoners of war also founded a camp university and a theatre. In the summer of 1941, an eleven-member archaeological working group was formed under the leadership of Louis-René Nougier (1912-1995), who discovered Mesolithic campsites within the camp during "walks" and analysed the finds in detail. Most of them were members of the Société préhistorique française, were in close contact with their association headquarters in Paris and were supported by the museum director Otto Damerau in Hoyerswerda. In July 1950, the working group of prisoner-of-war officers was able to report on their research in Oflag IV D at the 13th Congress of Prehistory in Paris.

Keywords: Germany, prisoner-of-war camp, Oflag IV D "Elsterhorst", French officers, Société préhistorique française, history of research, Mesolithic period.

Zusammenfassung: Zwischen Sommer 1940 und Frühjahr 1945 waren im Oflag IV D "Elsterhorst" bei Hoyer-swerda (Sachsen, Deutschland) etwa 5000 bis 6000 französische Offiziere interniert. Spuren des 30 ha großen, stacheldrahtumzäunten Lagers sind bis heute im Wiesengelände eines Segelflugplatzes erhalten und aus der Luft sichtbar. Dies gilt besonders für die Fundamente der Wohn- und Funktionsbaracken. Auf der Grundlage historischer und aktueller Luftaufnahmen ist eine exakte Lokalisierung und Georeferenzierung der Strukturen möglich. Da die Offiziere nach den Statuten der Genfer Konvention nicht zur Arbeit herangezogen werden durften, gab es zahlreiche Bereiche für unterschiedliche Aktivitäten wie etwa Gärten sowie Tennis- und Fußballplätze. Außerdem gründeten die Kriegsgefangenen eine Lageruniversität und ein Theater. Im Sommer 1941 bildete sich eine elfköpfige archäologische Arbeitsgruppe unter der Leitung von Louis-René Nougier (1912-1995), die innerhalb des Lagers bei "Spaziergängen" mesolithische Lagerplätze entdeckte und das Fundmaterial detailliert auswertete. Die meisten waren Mitglieder der Société préhistorique française, standen in engem Austausch mit ihrer Vereinszentrale in Paris und wurden von dem Museumsleiter Otto Damerau in Hoyerswerda unterstützt. Im Juli 1950 konnte die Arbeitsgruppe kriegsgefangener Offiziere auf dem 13. Kongress für Prähistorie in Paris von ihren Forschungen in dem Oflag IV D berichten.

Schlüsselbegriffe: Deutschland, Kriegsgefangenenlager, Oflag IV D "Elsterhorst", französische Offiziere, Société préhistorique française, Forschungsgeschichte, Mesolithikum.

12-2025, tome 122, 3, p. 389-404 - Allard P., Hromadová B., Nemergut A., Klaric L. (2025) – Slotted osseous points and pressure flaking technique for bladelet production in the Mesolithic in Eastern Slovakia (Medvedia Cave, Ružín)

Slotted Bone Points and Pressure Flaking for Mesolithic Bladelets in Eastern Slovakia (Medvedia Cave, Ru?ín)

Pierre Allard, Bibiana Hromadová, Adrian Nemergut, Laurent Klaric

Abstract: This article presents a new study of archaeological material from the Medvedia Cave (Ru?ín) in eastern Slovakia. This site is already known for its remains of Mesolithic brown bear hunting. The new study provides two radiocarbon dates proving the dual presence of a slotted osseous point associated with bladelets produced by pressure flaking during the Middle Mesolithic. Both results are consistent: Poz-907082 (point): 8580 ± 50 uncal BP i.e 7728-7532 cal BC (95,4 %); Poz-907099 (Bear skull): 8230 ± 50 uncal BP i.e. 7560-7400 cal BC (9.8 %) + 7376-7072 cal BC (85.6 %). These dates are unexpected for the Mesolithic in Slovakia. The identification of pressure flaking, which was used to produce small bladelets that were inserted into a long-grooved point of hard animal material, clearly evokes links with eastern and/or northern European Mesolithic cultures. The discovery of this type of point in eastern Slovakia gives rise to further questions when viewed in the context of the wider comparative evidence. This is particularly the case given that the Kunda or Grebenyky/Kukrek cultures, which are known to have produced similar slotted bone points with lithic inserts, are situated several hundred kilometres away.

Keywords: Mesolithic, Central Europe, lithic technology, pressure flaking, slotted bone point, 14C.

Résumé : Cet article présente une nouvelle étude du matériel du site de Medvedia en Slovaquie orientale. La grotte se situe dans le district de Ko?ice, sur la commune de Ru?ín. Avec le gisement de Barca, c?€?est l?€?une des rares occurrences de présence mésolithique dans l?€?Est du pays. Découverte par des spéléologues dans les années 1970, la cavité est composée d?€?un couloir d?€?entrée étroit orienté nord-ouest et long de 32 m qui est difficilement praticable. Ce passage débouche abruptement sur une salle (« la Chapelle ») qui se trouve 5 m en contrebas par rapport à l?€?entrée et correspond à un espace ovalaire d?€?au maximum 7 m de large. C?€?est dans cette partie que furent découvert les vestiges archéologiques datant du Mésolithique. Peu après la découverte de la cavité par des spéléologues, un crâne d?€?ours fut mis au jour au sein d?€?une couche de travertin de 40 cm d?€?épaisseur au sein de la Chapelle. En 1978, la société slovaque de spéléologie organisa une fouille pour récupérer le reste du squelette (appelé spécimen 1) Durant la fouille, les spéléologues récoltèrent également un fragment de lame en obsidienne ainsi qu?€?un « poinçon en os ». Juraj Bárta reconnut dans « le poinçon » un fragment de pointe en os à rainures longitudinales destinées à accueillir des lamelles en montage latéral. ?€ partir de 1980, il mena une fouille plus approfondie dans la Chapelle. Les restes de deux autres ours furent mis au jour. Outre ces vestiges fauniques, une seconde pointe à rainures latérales présentant 7 lamelles enchassées fut découverte à la limite des sondages A et B. Dans cet article, les deux pointes de projectile identifiées ont été observées en détails afin d?€?analyser les techniques de fabrication et d?€?identifier d?€?éventuelles altérations de surface. Le nouvel examen des lamelles a permis d?€?identifier la pression comme technique de détachement. Ces dernières sont particulièrement régulières, minces et étroites. Deux datations ont pu être réalisées, la première sur un fragment de la première pointe retrouvée (celle qui ne portait pas de lamelles) et la seconde sur le crâne d?€?ours auquel elle était associée. Les dates placent les artefacts dans le 8e millénaire avant-notre-ère : Ruzin_c.v.1 - Sagaie : 8580 ± 50 BP (Poz-97082) soit 7714-7533 cal. BC (95%) ; Ruzin_c.v.2 ?€? Crâne d?€?ours : 8230 ± 60 BP (Poz-97055) soit : 7454-7394 cal. BC (8.8%) et 7379-7077 cal. BC (86.6%) . Ces datations et la typologie des objets évoquent clairement des rapprochements avec les cultures mésolithiques orientales et/ou septentrionales. La position géographique de cette découverte pose question, puisque si l?€?on accorde du crédit aux comparaisons technologique et stylistique, les entités Kunda ou Grebenyky/Kukrek sont distantes de plusieurs centaines de kilomètres du site. En l?€?état, la grande nouveauté de ce réexamen de la petite collection de la grotte de Medvedia tient surtout à l?€?identification et, pour la première fois en Europe centrale, à la datation de la pression pour la production de lamelles à cette période.

Mots-clés : Mésolithique, Europe centrale, technologie lithique, débitage à la pression, pointe rainurée en os, C14.

11-2025, tome 122, 3, p. 369-388 - Mallye J-B., Marquet J.-C. (2025) – Un nouvel exemple de la consommation du spermophile au Tardiglaciaire dans les niveaux du Magdalénien supérieur du Bois-Ragot (Gouex, Vienne)

Un nouvel exemple de la consommation du spermophile au Tardiglaciaire dans les niveaux du Magdalénien supérieur du Bois-Ragot (Gouex, Vienne)

Jean-Baptiste Mallye, Jean-Claude Marquet

Résumé : La collection de restes de cet écureuil terrestre (Spermophile) provenant du gisement du Bois-Ragot a été réévaluée afin de documenter le statut de ce rongeur et de contribuer à comprendre les pratiques alimentaires et économiques des derniers chasseurs de renne en France. Il s'agit d'une grotte fouillée par André Chollet et Pierre Boutin jusqu'en 1990 considérée comme une séquence classique du Tardiglaciaire qui livre les témoins d'occupations répétées par les Magdaléniens et les Aziliens sur près de trois millénaires. Près de 800 restes de spermophile provenant majoritairement des niveaux magdaléniens ont été recensés. Des questions quant à la paléobiogéographie de cette espèce sont soulevées au regard de la présence de restes de cette espèce dans les niveaux aziliens.

Les restes de spermophile sont concentrés dans certaines zones du gisement, reflétant peut-être des zones d'activité humaine spécifiques. La représentation anatomique souffre de quelques manques qui peuvent être expliqués par un tri sélectif des gros ossements malgré une récolte aidée d'un tamisage fin. Les traces anthropogéniques et l'absence de traces de prédation non humaine indiquent que les spermophiles ont été accumulés par les groupes magdaléniens pour la consommation de la chair et probablement celle des peaux. Les carcasses ont été cuites à proximité d'une source de chaleur. Les données indiquent une occupation du site durant la bonne saison, et, tenant compte des résultats issus de l'analyse des autres denrées animales, il est envisagé une complémentarité dans l'acquisition des ressources tout au long de l'année. La présence de stries sur certains ossements pourrait traduire des modalités de préparation différentes pour certaines carcasses par séchage et la consommation différée de la viande. Elle met donc en hypothèse la possibilité de mise en réserve des ressources carnées issues de la petite faune.

La chasse estivale de ce rongeur et la possible mise en réserve de la viande impliquent 1) la planification des actions de chasse par la capture des animaux au meilleur moment de l'année et 2) la constitution de stocks en vue de pallier la raréfaction des denrées durant la mauvaise saison.

Mots-clés : Tardiglaciaire, Magdalénien supérieur, spermophile, archéozoologie, petit gibier, trace de découpe, trace de cuisson, stockage.

Abstract: The end of the Late Glacial in south-western Europe was marked by rapid climatic changes that had a significant impact on environments and animal communities. During this period, game hunting was mainly dominated by the acquisition of large ungulates. However, the capture of smaller game animals, such as small mammals, birds or fishes, became more systematic and, in some cases, even more intensive. Among the small game hunted, the ground squirrel has a special place in several sites occupied by the last hunter-gatherers from the Magdalenians period. The aim of this study is to re-evaluate the collection of ground squirrel remains from Bois-Ragot cave in order to document its status among the known species and to help us to understand the dietary and economic practices of the last reindeer hunters in France. The Bois-Ragot cave was excavated by André Chollet and Pierre Boutin until 1990. It provides evidence of repeated human occupation at the end of the Late Glacial. This site can be considered as one of the classic Late Glacial sequences, yielding lithic artefacts animal remains and bone industries of repeated occupation by hunter-gatherers during the Magdalenian and Azilian occupations over nearly three millennia. The excavation revealed 4 levels, two of which were late Magdalenian and two Azilian, each characterized by its own tools and a faunal spectrum that more or less reflects local climatic and environmental variations.

This study resulted in the identification of almost 800 ground squirrel remains, mostly from Magdalenian levels. The remains are relatively well preserved, with a low fragmentation rate. The distribution of the remains shows concentrations in certain areas of the site, perhaps reflecting specific zones of human activity. The anatomical representation suffers from a few weaknesses, which can be attributed to the selective sorting of the largest bones, despite a recovery assisted by fine sieving. The age of the ground squirrels was estimated by dental maturity and the degree of ossification of the long bones. We were able to show that most of the individuals were captured before their first hibernation, suggesting that they were hunted during the good season. Anthropogenic marks on the bones, such as cutmarks and burning marks, indicate human consumption of ground squirrels. The presence of ground squirrel remains in the Magdalenian levels of Bois-Ragot is not in itself surprising, as other contemporary sites have previously yielded such remains. However, their presence in the Azilian levels raises questions about the paleobiogeography of this species. Post-Magdalenian ground squirrel remains have only been mentioned at the Pont d'Ambon; as these are small remains, it is difficult to be fully certain of their strict contemporaneity with the surrounding remains. In addition, contamination of Azilian remains in the Magdalenian level and vice-versa has been documented at this site. Direct radiocarbon dating of these remains could therefore be envisaged, which would help to fully document the paleobiogeography of this ground squirrel during the Late Glacial.

At Bois-Ragot, anthropogenic marks and the absence of traces of non-human predation indicate that ground squirrels were accumulated by Magdalenian groups for the consumption of meat and probably skins. The carcasses were cooked close to a heat source. The data indicates that the site was occupied during the good season and, taking into account the results of the analysis of other animal products, it is possible that resources were acquired throughout the year. The presence of striations on certain bones when the flesh can be removed with the aid of teeth alone is discussed. These striations could reflect different methods of preparing certain carcasses by drying and delayed consumption of the meat. It therefore suggests that meat resources from small fauna could have been stored.

This study adds the ground squirrel to the hunting list of the last Magdalenian hunter-gatherers and sheds light on their dietary and economic practices. It shows how the expansion of the human diet at the end of the Palaeolithic included a variety of small game, reflecting an adaptation to the environmental and social changes of the time. The summer hunting of this rodent and the possible hoarding of its meat meant that hunting activities had to be planned to capture animals at the best time of year, but also that stocks had to be built up to compensate for the scarcity of food during the off-season.

Keywords: Late Glacial, Upper Magdalenian, ground squirrel, zooarchaeology, small game, cutmaks, cooking marks, storage.

10-2025, tome 122, 3, p. 335-367 - Meignen L., Bourguignon L., Mann A., Maureille B. (2025) – La séquence du Moustérien Quina des Pradelles (Marillac-le-Franc, Charente) : approche techno-économique des industries

La séquence du Moustérien Quina des Pradelles (Marillac-le-Franc, Charente) : approche techno-économique des industries

Liliane Meignen, Laurence Bourguignon, Alan Mann, Bruno Maureille

Résumé : L'étude des outillages lithiques présentée ici concerne la totalité des occupations humaines identifiées dans le site des Pradelles (lithofaciès 2 et 4), par ailleurs connu pour les nombreux restes humains néandertaliens mis au jour. La confrontation de ces nouvelles données techno-économiques avec celles des études archéozoologiques déjà publiées permet de préciser les activités menées sur le site tout au long de la séquence.

Quatre lithofaciès (faciès 2a, 2b, 4a, 4b) y ont été identifiés qui se situent probablement à la fin du MIS 4 (2a) et au début du MIS 3 (2b à 4b), jusqu'à -55 ka environ (datations OSL et IRSL).

Les travaux antérieurs avaient mis en évidence, dans les niveaux de base de la séquence, un Moustérien de type Quina qui, associé à de très nombreux restes de rennes, montrait une gestion différentielle des matières premières. Sur la base des données de l'étude du lithique et de celle des restes osseux, ce site a alors été considéré comme une halte de chasse spécialisée dans le traitement des carcasses de rennes en vue d'une consommation différée. Les Néandertaliens y ont aussi traité certains de leurs congénères de façon similaire aux ongulés.

L'étude techno-économique présentée ici indique que les outillages provenant des quatre niveaux lithostratigraphiques nouvellement définis lors des recherches de terrain entreprises entre 2002 et 2012 montrent des caractéristiques comparables dans leurs grandes lignes, tout au long de la séquence. Les groupes de Néandertaliens qui ont fréquenté le site de façon répétitive appartiennent tous à une même tradition technique, le Moustérien de type Quina.

Les faibles densités de matériel lithique qui contrastent fortement avec l'abondance des restes osseux, les stratégies de gestion des matières premières comparables dans tous les niveaux, suggèrent des occupations de courte durée, motivées par le même objectif. Ces stratégies d'acquisition/gestion des outillages reposent sur l'introduction de matériaux exogènes, sous diverses formes, complétée par une production sur site, en matériaux locaux de moindre qualité, plus ou moins dominante selon les niveaux.

Cependant, les études détaillées présentées ici font apparaître, selon les niveaux considérés, des différences d'ordre techno-économique, identifiées dans la gestion des matières premières, et en particulier dans le séquençage des chaînes opératoires.

Ainsi dans les niveaux inférieurs (faciès 2), les activités sont diversifiées, avec une part importante de la production de supports réalisée sur place (débitage, recyclage) mais aussi une activité d'entretien des outils, quelle que soit la matière première. Durant les activités réalisées lors de la mise en place du faciès 4 (niveaux supérieurs) au contraire, au sein desquelles les proportions de produits importés sont nettement plus marquées, ce sont les activités de maintenance (et en particulier, aménagement et réaffûtage des racloirs Quina en matériau exogène) qui dominent. Ces derniers éléments témoigneraient, dans les niveaux supérieurs, d'activités de traitement des peaux sur site plus importantes que dans les niveaux inférieurs.

La confrontation des données archéozoologiques avec celles du lithique montrent que dans ce site d'activités spécialisées (campement temporaire saisonnier lié à l'exploitation des rennes interceptés lors de leur migration), ce sont les activités de boucherie secondaire qui dominent (sur les éléments de carcasses importées, prélèvements de filets, de tendons ; fracturation des ossements pour l'exploitation de moelle et graisse ; récupération des extrémités articulaires ; fabrication/utilisation de retouchoirs en os), ainsi que le traitement partiel des peaux. Une dissociation des activités dans l'espace est observée : boucherie primaire (hors cavité, sur le site d'abattage), boucherie secondaire (dans une partie de la cavité) et travail des peaux (probablement partiellement hors cavité) impliquant un flux des différents éléments de carcasses animales, et en parallèle, celui de l'outillage lithique impliqué dans chacune des étapes de traitement (import et exportation de racloirs Quina en particulier).

Le caractère répétitif de ces activités en un même lieu ou à très grande proximité, ainsi que les stratégies de gestion des matières premières, suggèrent une organisation structurée de l'espace régional dont les ressources sont connues et leur exploitation planifiée. Le site des Pradelles aurait alors occupé une place très particulière dans le cycle annuel de ces chasseurs-cueilleurs destinée à la constitution de réserves alimentaires utilisées durant les périodes de pénurie. L'ensemble des comportements décrits témoigne incontestablement chez ces Néandertaliens d'une double anticipation des besoins, techniques et alimentaires. Pour le moment, Les Pradelles est incontestablement un site moustérien sans équivalent en région Nouvelle-Aquitaine.

Mots-clés : Moustérien Quina, Charente, techno-économie, gestion des matières premières et des outillages, rapport lithique-faune, comportements néandertaliens.

Abstract: The lithic study presented here concerns all the human occupations identified at the Pradelles site (lithofacies 2 and 4) during the Maureille-Mann excavations (2002-2012), which is also known for the numerous Neandertal remains. By comparing these new techno-economic data with previously published archaeozoological studies allows for a more precise understanding of the activities carried out at the site throughout the sequence.

Four occupation levels have been identified, which likely date to the end of MIS 4 and the beginning of MIS 3, around 55,000 years ago (OSL and IRSL datings).

Previous work carried out on material from the Vandermeersch excavations (1967-1980) had highlighted a Quina-type Mousterian in the lower part of the sequence (layer 9-10), which, associated with a large number of reindeer remains, demonstrated a differential management of raw materials (local and exogenous flints). Based on lithic data and the study of faunal remains, the site was considered as a specialized seasonal temporary camp devoted to reindeer carcass processing for delayed consumption. Neandertals also processed some of their own kind in a manner similar to ungulates.

The techno-economic study presented here shows that the tools from the four newly defined lithostratigraphic levels (Maureille-Mann excavations) have techno-typological characteristics that are broadly comparable throughout the Pradelles sequence. The Neandertal groups that repeatedly visited the site all basically belong to the same technical tradition, the Quina-type Mousterian. The very low densities of lithic material, which contrast sharply with the large quantities of bone remains, and the comparable techno-economic structure of the lithic assemblages across all levels suggest repeated short-term occupations driven by the same goal.

The strategies for acquiring and managing tools rely on the introduction of non-local flint in the form of already retouched products or large flakes which are later retouched/resharpened or recycled on site ("multipurpose matrices"). This exogenous component is complemented by on-site production using locally available, lower-quality flint, with varying dominance across the levels. The retouched tools are largely dominated by scrapers, which are very abundant in the exogenous flint series, often with a characteristic retouch, the Quina and semi-Quina retouch, specifically developed on imported materials.

These tool management strategies, which show the introduction of a range of lithic products in already elaborated form (flakes, scrapers, matrices), which were subsequently recycled or largely maintained on-site, are clearly reminiscent of the transport of basic equipment observed in modern hunter-gatherers, named "personal gear" by Binford as part of a "provisioning of individuals" strategy.

However, the new, more detailed studies presented here reveal techno-economic differences, depending on the level considered, in the management of raw materials and, in particular, in the spatial and temporal fragmentation of the reduction sequences.

In the lower levels (facies 2), activities were diversified, with a significant proportion of the blank production taking place on-site (flintknapping, recycling), as well as tool maintenance activities, regardless of the raw material.

In contrast, during the activities associated with the deposition of lithofacies 4 (upper levels), where the proportions of imported materials are notably higher, maintenance activities (particularly the modification and re-sharpening of Quina scrapers made from exogenous materials) dominate. These latter elements would suggest that, in the upper levels, on-site hide processing activities were more prominent than in the lower levels.

The comparison of archaeozoological data with lithic data shows that at this task-specific location (a temporary seasonal camp related to the hunting of reindeer during their migration), secondary butchery activities dominated (on imported carcass elements, collection of tendons ; bone fracturing for marrow and fat extraction; recovery of joint extremities; manufacture and use of bone retouchers), as well as partial hide processing.

A spatial dissociation of activities is observed: primary butchery (outside the site and near of the killing place), secondary butchery (in a part of the site), and hide processing (probably partially outside and near the site), involving the flow of various carcass elements and, in parallel, the movement of lithic tools used in each processing stage (import and export of Quina scrapers in particular).

The repetitive nature of these activities in the same location or in very close proximity, along with the raw material management strategies, suggests a structured organization of the regional space, with known animal and mineral resources and planned exploitation. The Pradelles site likely played a very particular role in the annual cycle of these hunter-gatherers, contributing to the formation of food reserves used during periods of scarcity. The behaviors described undeniably reflect a dual anticipation of both technical and dietary needs by these Neandertals. For now, Pradelles is undoubtedly a Mousterian site with no equivalent in the Nouvelle-Aquitaine Region.

Keywords: Quina type Mousterian, Charente, techno-economy, lithic technological organization, raw material economy, lithic-fauna relationships, Neandertal behavior.

09-2025, tome 122, 2, p. 253-289 - Pailler Y. et al - Brisons la hache et enterrons-la ! Autopsie et réflexions autour du dépôt d?€?une grande lame polie en fibrolite à Kerarmerrien (Plouzané, Finistère)

Brisons la hache et enterrons-la !

Autopsie et réflexions autour du dépôt d'une grande lame polie en fibrolite à Kerarmerrien (Plouzané, Finistère)

Yvan Pailler, Stéphan Hinguant, Manon Mabo, Arnaud Agranier, Vincent Bernard, Emmanuelle Collado, Rozenn Colleter, Laurence David, Olivier Poncin, Alison Sheridan, Christophe Bontemps

Résumé :

Dans le cadre d'un diagnostic archéologique réalisé à Kerarmerrien, sur la commune de Plouzané (Finistère), a été mise au jour une remarquable lame polie en fibrolite, brisée en deux. Découverts à environ 0,40 m de profondeur sous la surface actuelle, les deux fragments n'ont pas été affectés par les labours modernes et se trouvaient à quelques centimètres l'un de l'autre. Ils se raccordent parfaitement, sans aucun manque, et forment une grande lame polie en forme de goutte d'eau. Une extension du décapage autour de la découverte et la fouille fine de la zone ont permis de confirmer que la pièce est totalement isolée et ne provient pas du comblement d'une quelconque structure. Le tranchant, bien que légèrement émoussé, mais sans trace de réaffûtage, laisse à penser que nous sommes face à un objet peu ou non utilisé. De même, la lame présente un polissage luisant sur toute sa surface hormis l'extrémité du talon qui conserve encore quelques petites plages brutes. Enfin, si la cassure présente un aspect frais, la patine qui affecte les surfaces atteste son ancienneté. Si nous ne pouvions pas exclure a priori la cassure accidentelle de la lame lors de son utilisation, il semble plus pertinent de nous orienter vers une autre interprétation, celle du bris puis du dépôt de l'objet, envisagés comme des gestes intentionnels. L'analyse typo-technologique, la pétrographie et les comparaisons régionales et inter-nationales sont sollicitées pour tenter d'identifier un scénario. Considérant la position topographique singulière du lieu de la découverte, sur une ligne de partage des eaux et très proche des sources de l'Ildut, la lame polie de Kerarmerrien pourrait en effet témoigner d'une pratique rituelle au Néolithique, celle du dépôt d'un objet socialement valorisé fait aux puissances surnaturelles.

Mots-clés : grande lame polie, imitation du type Durrington, fibrolite, pétro-archéologie, technologie lithique, Néoli-thique ancien/moyen, dépôt isolé, bris de la hache, acte sacrificatoire, Bretagne.

Abstract:

During exploratory excavation of an area of 23 ha at the north-west tip of Brittany, at Kerarmerrien in Plouzané commune, two fragments of a large polished axehead were found in undisturbed ground around 40 cm below the surface. In such a large stripped area, it is remarkable that no arrangement or concentration of Neolithic material was found; this shows that the object had been deposited on its own. The only other evidence for the presence of Neolithic people consisted of several hearths with heat-damaged stones in the surrounding area; these are most likely to date to the Early or Middle Neolithic, to judge from the latest radiocarbon dates. The deposition of this axehead was situated close to the sources of the coastal river Ildut, in a large marshy depression where there is no evidence for a permanent presence of people during the Neolithic. The technical analysis of the axehead shows that it was deliberately broken in two before being buried, and the act of breakage involved a particularly strong transverse blow. The two fragments, which conjoin perfectly with one another, were laid down side by side and head-to-tail, showing a clear intention to position them. The axehead, of an exceptional size (almost 23 cm long), must have taken hundreds of hours to manu-facture, involving hammering, sawing and polishing. Macroscopically, the raw material is a massive fibrolite, green-ish-yellow with brown patches; its interdigitated fibrous structure is typical of that seen at the outcrops at Plouguin. The results of geochemical analyses (by XRF and Raman spectrometry), compared with those of several raw material samples collected through prospecting, confirm that this is a sillimanite with muscovite, identical to that of the Plouguin outcrops, and more specifically to those at Lanrivanan, in the same commune, just 19 km to the north of the axehead findspot as the crow flies. The axehead, obtained through sawing (as is shown by the asymmetry of its cross-section), is in the form of a teardrop, reminiscent of the Durrington type of axehead made from Alpine rock. The Durrington type, like the Heilles type with which the axehead also shares formal similarities, had a fairly long currency, appearing during the Early Neolithic and disappearing during the Middle Neolithic 2. There is evidence for Neolithic activity during this period in bas Léon, with the number of B-VSG finds multiplying, while the Middle Neolithic evidence (in the form of passage tombs, arrangements of standing stones, settlements and fish weirs) reveals a certain patterning in the spatial organisation of activities.

The Kerarmerrien find spurred us to re-examine the deposits of axeheads that had been made in Brittany, comparing them with deposits of axeheads made from Alpine rocks that have recently been the subject of synthesis and thorough documentation by JADE project (directed by Pierre Pétrequin). Our attention was drawn to an old find (1970), of a complete axe with its haft, brought to the surface through shallow dredging in the Trieux estuary (Côtes-d'Armor), next to a bog. This is known only from a brief mention in a publication. While the haft could not be conserved, photographs taken shortly after its discovery allow us to make out its shape and size, and to draw a parallel with axes known in the Pfyn culture (Switzerland) dating to the first third of the 4th millennium; in these, the head was slotted directly into the haft and the upper end of the haft curves backwards slightly. The large axehead that was found in its haft at Trieux had a perfectly sharp blade and was made from a chrome-rich muscovite with sillimanite -- the chrome explaining the very green patches visible on the surface -- which points towards the outcrops of Plouguin, in north-west Finistère, as the origin. Rather than imagining a simple loss of this tool as someone crossed a small coastal river, it seems to us more likely that we are dealing with a case of deliberate deposition, connected with the water.

Several other findspots in Armorica and elsewhere suggest a deliberate choice of location for axehead deposition (the commonest being on high ground, or close to water, or at a rocky outcrop or beside a standing stone), generally at some distance from settlements or tombs. While the location of the findspot was important, it seems that the manner in which the axeheads were deposited similarly played a key role. Here, the observations made in situ at Plouzané, Carentoir and Lannion offer new insights on the complex question of depositional practices. To this we can add instances where axeheads have been associated with objects that do not seem special but which appear to us, with our prehistorians' eyes, to relate to the everyday. But, finally, what do we know of the biographies of these polished axeheads outside of their place of discovery; of their chaîne opératoire; and, in certain cases, of the outcrops from which their raw material had been extracted?

Keywords: large polished axehead, teardrop shape, fibrolite, petro-archaeology, lithic technology, Early/Middle Neolithic, isolated deposition, breakage of an axehead, sacrificial act, Brittany.

08-2025, tome 122, 2, p.233-252 - Ghesquière E., Flotté D., Giazzon D., Granai S., Jamet G., Vissac C. (2025) – Mise en évidence de Schlitzgruben du Néolithique moyen sur le site des Jardins de Clopée Z3 de Giberville (Calvados)

Mise en évidence de Schlitzgruben du Néolithique moyen sur le site des Jardins de Clopée Z3 de Giberville (Calvados)

Emmanuel Ghesquière, David Flotté, David Giazzon, Salomé Granai, Guillaume Jamet, Carole Vissac

Résumé :

La fouille d’une grosse occupation du Bronze ancien du site des Jardins de Clopée Z3 à Giberville, en 2020, a été l’occasion d’intervenir sur un nombre important de fosses en fente/Schlitzgruben qui font l’objet d’une présentation dans cet article.

Ces fosses longues, profondes et étroites se retrouvent sur tout le territoire national mais de façon beaucoup plus impor-tante dans la moitié nord de la France. Leur fonction ne fait pratiquement plus débat et il semble désormais acquis qu’elle soit celle de fosses de chasse utilisées pour le piégeage des grands mammifères. Elles apparaissent au début du Mésolithique récent, en remplacement des fosses cylindriques ou tronconiques ; leur présence s’accentue durant le Néolithique. Ces fosses témoigneraient ainsi de la persistance parfois importante de la pratique cynégétique parmi les populations agricoles.

Dans un premier temps, l’article s’attachera à discuter certaines problématiques concernant ces fosses. Dans un second temps, la description du site permettra de mettre en avant les différentes composantes de ces structures, de leur répar-tition en vastes systèmes organisés à leur morphologie propre. Les datations restent assez lacunaires sur ces fosses, tributaires des charbons piégés à la base de leur remplissage. Elles semblent ici confirmées par l’analyse malacologique, qui précise également leur implantation dans ou en bordure d’un secteur boisé. L’article conclura sur l’évolution de ces fosses sur le site durant le Néolithique moyen (4600-3400 cal BC) et leur inscription au cœur d’un paysage partielle-ment anthropisé.

Cet article n’a pas pour vocation de synthétiser l’ensemble des problématiques et des données concernant les Schlitzgruben au niveau national ni même régional, mais plutôt d’offrir de la visibilité sur un site précis, qui livre plu-sieurs systèmes de fosses en fente, décapés dans leur intégralité.

Mots-clés : Schlitzgruben, fosses de chasse, Néolithique moyen, système de fosses, datations radiocarbone, malacologie.

Abstract:

Several surveys and excavation operations were carried out on around a hundred hectares on the plateau between the municipalities of Giberville and Colombelles, in an openfield landscape dedicated to intensive cereal agri-culture. This geographical area is located on the outskirts of the city of Caen, in Normandy. Many occupations have been excavated on this site: a Roman villa, five Gallic farms and a set of small Early Bronze Age enclosures with asso-ciated funerary structures. In one of the largest excavation windows, several distinct systems of slit pits/Schlitzgruben were highlighted. These pits have the particularity of having a very elongated ovoid plan, a significant depth and very slightly flared sides. Two of these systems are recorded in the form of arched lines and another in the form of clusters, in addition to a few scattered pits. Schlitzgruben, from German literally designating a slit pit, is a structure with a length 2 to 5 times greater than its width. Its transverse profile is narrow and more or less deep, depending on the type (V, Y, I profile). Its longitudinal profile is either a regular deep bowl or a W-shaped one, with a less hollow central reserve. Its use as a hunting trap is generally adopted.

Added to this is a possible incomplete line highlighted in another diagnostic window and in the stripping process. Following the excavation of all the pits and due to the lack of material, the chrono-cultural attribution is based on a few radiocarbon dates of charcoal discovered at the base of their filling. Despite doubts about some of these dates, the inscription of these systems over the entire duration of the Middle Neolithic seems to be confirmed by the malacologi-cal study. A micromorphological study, linked to one of the Schlitzgruben, did not provide any traces of specific devel-opments. Furthermore, a concentration of large windfalls over an area of 1600 m2 in the excavation window would indicate the presence of a dense grove on the edge of the Schlitzgruben systems. The few dates carried out suggest

Keywords: eco-cultural niche modelling, prehistory, Gravettian, Rayssian, culture/environment relationships, rapid climate change.

07-2025, tome 122, 2, p.203-232 Godard C., Gonnet A., Fechner K. (2025) – Nogent-sur-Seine (Aube), site du Cardinal II : des fosses pré- et protohistoriques comme témoins de l’évolution des sols et des paysages au cours de l’Holocène

Nogent-sur-Seine (Aube), site du Cardinal II : des fosses pré- et protohistoriques comme témoins de l’évolution des sols et des paysages au cours de l’Holocène

Céline Godard, Adrien Gonnet, Kai Fechner avec la collaboration de Salomé Granai et Sylvie Coubray

Résumé :

La mise au jour d’une série de fosses profondes datées du Mésolithique ancien et moyen, ainsi que du Néolithique et de l’âge du Bronze ancien à Nogent-sur-Seine (Aube, Grand Est) a permis d’appréhender ces structures comme des archives sédimentaires des sols anciens, aujourd’hui disparus. À travers une approche transdisciplinaire combinant les méthodes des géosciences et de l’archéologie environnementale, ces structures laissent entrevoir l’évolution des sols et de l’environnement intra-site, et permettent de replacer les différentes occupations dans leurs contextes paysagers. Cette approche a mis en évidence des traits pédologiques spécifiques pour les structures du Mésolithique, notamment des taux importants de carbonates secondaires mesurés par calcimétrie, associés à des comblements humi-fères issus d’un sol forestier particulièrement développé au Préboréal et au Boréal. La confrontation des mesures calcimétriques réalisées sur le comblement des fosses avec les âges mesurés par datation absolue révèle une bonne corrélation entre âge des structures et degré de carbonatation secondaire, et la décarbonatation progressive des sols. L’évolution pédologique transforme les dépôts lœssiques du terrain naturel encaissant à partir du Mésolithique moyen avec la mise en place d’un luvisol et d’un horizon argilique (horizon Bt). Cette évolution pédologique, à corréler avec l’optimum climatique de l’Holocène, affecte la partie supérieure des comblements des fosses mésolithiques les mieux conservées. Cette stabilité est renforcée par un milieu boisé où plusieurs essences se mêlent (perduration du pin, bouleau, puis chênaie mixte) comme l’illustrent les écofacts et les indicateurs malacologiques. Cet horizon Bt est également observé à l’échelle macro- et microscopique sous une forme remaniée dans le remplissage des structures du Néolithique ancien et moyen. Enfin, la seconde moitié de l’Holocène, à partir de l’âge du Bronze, est caractérisée par un milieu semi-ouvert, en partie anthropisé, où les premières phases d’érosion se mettent en place progressivement avant une déstabilisation généralisée des sols au Subatlantique, à la faveur d’un milieu majoritairement ouvert et anthropisé.